In late March 1945, 300 Japanese soldiers appeared suddenly out of the dark near Hirawa Bay on the island of Iwo Jima, catching an encampment of US Marines and Army Air Force personnel completely by surprise. A vicious firefight ensued, not ending until the last attacker was killed three hours later. The Americans suffered 170 dead and wounded.

That was 36 days after three Marine divisions (and later an independent U.S. Army infantry regiment), after the conclusion of the longest sustained aerial offensive of the war, and preceded by an unprecedented amount of naval bombardment and subsequent gunfire support, had begun their landings.

The Marines hit the beach on February 19th. The desperate attack by the starving remnants of Iwo’s Japanese defenders took place five weeks later.

The victors took stock as the sun rose. The bloody skirmish near Hirawa Bay was fought some two miles away from where the Marines had bottled up the last stubborn Japanese resistance on the volcanic rock. This particular Japanese force apparently slipped the American noose, likely made their way through a warren of underground tunnels (dug by hand), and crept down the island’s west coast, looking for a target of opportunity.

It was the final fight of the Battle of Iwo Jima. It placed an appropriately violent exclamation point on what was perhaps the most brutal campaign of history’s most destructive war. Blood-soaked Iwo Jima, the so-called “Sulfur Island,” had finally fallen.

Cover photo above: 2/7 Marines (2nd Battalion, 27th Marines) landing on Iwo Jima as part of the first wave, February 19th, 1945. The original black and white photo was taken by Bob Campbell and taken from the Signal Corps Archive. This version was colorized by @colourizedjackson.

Battle of Iwo Jima: Why take “Sulfur Island”?

The official name of the campaign to take Iwo Jima was Operation Detachment.

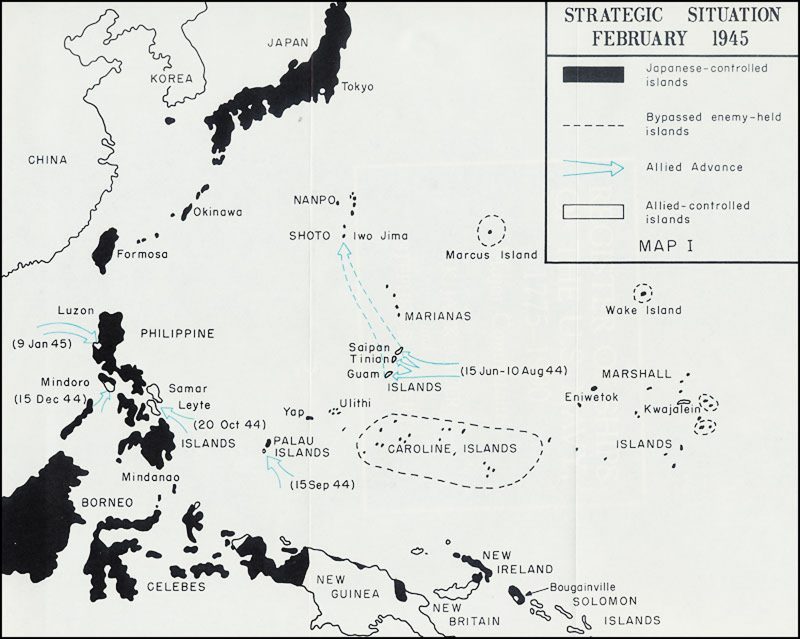

Part of the Volcano subgroup of the Bonin Island chain, Iwo Jima had no seeming value apart from its location along the strategic bombing routes between the Mariana Islands and the Japanese homeland – but the significance of its location along that route cannot be understated.

The eight square miles of rock and volcanic ash lay 625 nautical miles north of Saipan and 660 nautical miles south of Japan itself. American air planners quickly identified Iwo’s potential as an emergency landing spot for damaged B-29 bombers, as well as a base for long-range P-51 Mustang escort fighters. In fact, it was the only island on the route with terrain suitable for B-29-capable airfields.

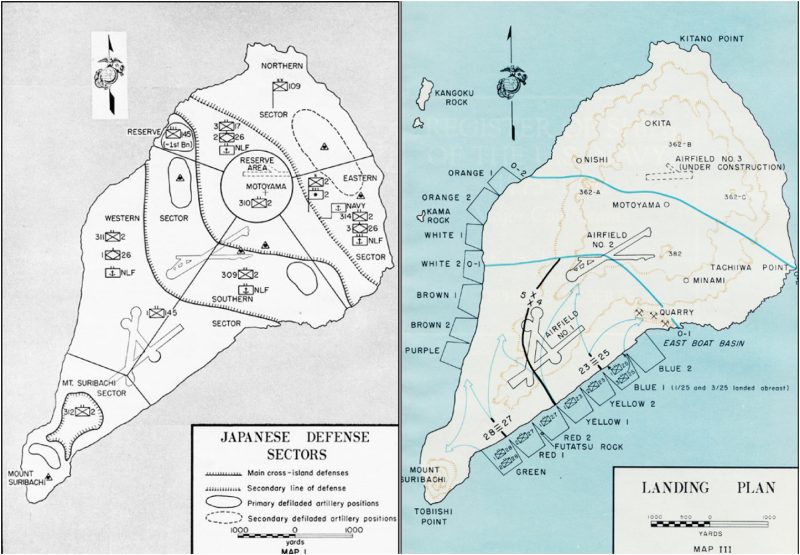

The planners also recognized that Japanese fighter aircraft could be stationed on Iwo, forcing the B-29s to run longer routes to avoid them. The Japanese had, in fact, built two airfields on the island, with a third under construction when the Marines landed on February 19, 1945. These factors convinced the American brass, who slated Iwo Jima for invasion.

Fortress Pacifica

Japanese planners could also read a map. They had long identified Iwo Jima as vital to the Home Islands’ outer defenses. The US Navy’s Central Pacific thrust through the Gilbert and Marshall Islands clearly pointed toward the Marianas. Were the Japanese unable to stop the Americans there, the offensive would turn north, and Iwo Jima lay in its path.

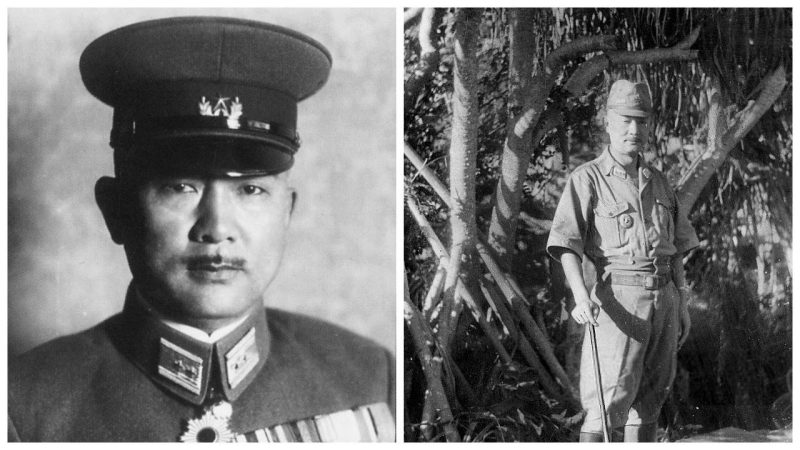

The Imperial Japanese Army accordingly sent one of their most experienced commanders, Lt. General Tadamichi Kuribayashi, to fortify Iwo against that threat. Kuribayashi arrived on June 13, 1944, two days before the US 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions hammered their way ashore on Saipan.

Kuribayashi was among the first Japanese commanders to learn the hard lessons of fighting the American amphibious machine. He understood that the US Navy would command the sea and the sky. He also knew the enemy ships would rain large-caliber naval gunfire onto his troops with impunity, accompanied by constant airstrikes. The old doctrine of trying to stop the Americans at the water’s edge had been violently repudiated everywhere they had tried it. The Marines would get ashore.

The Japanese commander therefore decided to use the island itself to protect his men. Aided by mining engineers, they improved and reinforced Iwo’s natural caves and dug 16 miles of connecting tunnels. Digging in round-the clock shifts, Kuribayashi’s men built underground barracks, staging areas, supply dumps, and command posts.

They also created hundreds of mutually supporting fighting positions, pillboxes, and blockhouses, which were manned and reinforced through the tunnel system. Tons of rebarred concrete made these positions even more formidable. Kuribayashi arrayed his defenses in belts leading south to north from the invasion beaches, which were obvious to his trained eye. He personally sighted lines of fire, around which he designed each belt as the ground widened and rose from south to north, culminating in the final redoubt around the Motoyama Plateau, some 350 feet above sea level. Kuribayashi took full advantage of natural ravines and outcroppings, while adding anti-tank ditches to deny the Marines their armor support.

Mount Suribachi, a 550-foot tall dormant volcano on Iwo Jima’s southern tip, dominated the entire island. Kuribayashi ringed Suribachi’s base with interlocking concrete pillboxes, with dug-in fighting positions along the mountain’s slope.

Protected artillery embrasures and armored casemates dotted the landscape, containing everything from traditional mortars and field guns to gigantic 320mm “spigot mortars.” The heavy stuff was mostly concentrated around the Motoyama Plateau and on Mount Suribachi. They could reach anywhere on the island at any time.

Finally, at the Japanese Navy’s insistence, Kuribayashi had his men build a line of reinforced pillboxes along the island’s southern airfield. US airstrikes and cruiser raids had demolished parked Japanese aircraft, so the wrecked airframes were converted into makeshift defenses between the concrete emplacements. This line dominated most of the landing beaches and the approaches heading north.

The work was brutal. Despite Suribachi’s dormancy, Iwo Jima was still geologically active, making underground work incredibly taxing as temperatures rose to up to 140 degrees. Sulfuric steam vents poisoned the air and added a sickening stench. Water had to be shipped in while the troops collected what rainwater they could. Groundwater was sulfurous. Water was strictly rationed and there was never enough. The soldiers could only dig in 10-minute shifts before needing to ascend for fresh air. But eight months of steady work produced the desired results.

Iwo Jima was the most heavily defended fortress on Earth. Its defenders could not be outflanked. The Americans could only attack them frontally. And unlike earlier Japanese commanders, Kuribayashi would not throw his men away in pointless Banzai charges over open ground. He would force the Marines to dig his 22,500 men out, one position at a time.

Battle of Iwo Jima: the Assault Force

The US Marine Corps of World War II was an amphibious shock troop force. By mid-1944, they were unparalleled in that role. The US Navy was also the world’s premier amphibious support force, with dedicated naval bombardment groups and experienced close air support units. Getting the Marines ashore under fire was a well-honed science by the time Iwo Jima hove into view in the early morning of February 19, 1945.

Major General Harry Schmidt, commanding the V Amphibious Corps (VAC), had a good idea how stout Iwo Jima’s defenses were. Aerial photos clearly showed that the enemy were underground. The Japanese had employed similar tactics on Peleliu the previous autumn, all but wrecking the veteran 1st Marine Division, which had to blast them out of the island’s coral caves.

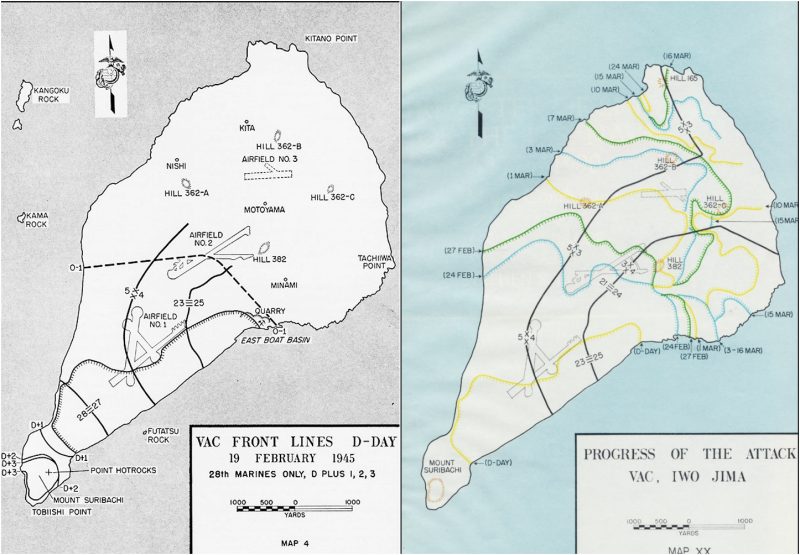

The 1st Marine Division had, in fact, been initially slotted to invade Iwo Jima, but the unexpected casualties at Peleliu forced their replacement by the green 5th Marine Division. The 4th Marine Division formed the other half of the assault force, with the 3rd Marine Division as a floating reserve. The 5th Division was assigned the left flank, which included taking Mount Suribachi and the island’s western half. The 4th Division landed on the right, assigned to the eastern half. The landing force totaled some 111,000 men, with another 36,000 in the Army garrison force, which relieved the Marines on March 26.

Schmidt requested a minimum of ten days of continuous naval preparatory fire before the Marines landed. The top Marine in the Pacific, Lt. General Holland M. Smith, backed him in that request. Smith’s job was to liaise with Rear Admiral Kelly Turner, the amphibious force commander. Smith and Turner were perhaps the world’s foremost amphibious warfare experts at the time.

But Admiral Raymond Spruance, commanding the US Fifth Fleet, refused to risk his ships on station that long, knowing they’d be a prime target for Japanese submarines. US Navy doctrine correctly held that the greatest threat to an amphibious landing’s success was a strike at the invasion fleet. The Japanese had tried that tactic at Guadalcanal, Saipan, and Leyte Gulf.

Despite some very tense moments, the Americans had turned them away each time, inflicting crushing defeats in the process. The Japanese Navy was incapable of offensive operations so far from home after Leyte Gulf, five months previously, though Spruance’s concern over submarines had some merit. The admiral also worried about his ships running out of ammunition, though the Navy had mastered resupply at sea by that time. This especially incensed Holland Smith.

Whatever the reason, Spruance only allowed three days for naval preparatory fire. He refused to extend it, despite his Task Force 58 launching punishing carrier raids on Tokyo itself a few days prior, with no real resistance from the Japanese.

But carrier airstrikes and heavy bombers pounded the island for a week prior to D-Day. And the naval bombardment buried Iwo Jima under clouds of dust and smoke, punctuated by bright explosions. Veteran war correspondent Robert Sherrod remarked that it was “more terrifying than any other similar spectacle I had ever seen.” The Marines hoped it would be enough.

D-Day: February 19, 1945

Eight Marine battalions from four regiments loaded up and moved toward the beach at 0840. The entire first wave was landed in 90 minutes, including a tank battalion and part of an artillery battalion. The beaches seemed lightly defended at first. That soon changed.

As the Marines stacked up on the beach, they began taking fire from every direction as Kuribayashi’s dug-in emplacements opened up. Pre-registered artillery fire from Mount Suribachi and the Motoyama Plateau landed along the entire beachhead with devastating results, having waited for landing force to bunch up.

Marines tried to move inland, but the beach wasn’t sand. It was soft volcanic ash, into which their boots sank up the laces. Tanks had trouble getting purchase. The island’s topography made things worse, as the beach rose in a series of ash terraces, through which the attackers could only move slowly. There was no cover apart from destroyed American materiel. Digging in the ash was useless. One Marine likened it to digging in a barrel of wheat. Machine gun fire raked those who tried to move. Mortar rounds pounded those who didn’t. Those included the 320mm “spigot” mortars, whose 675-pound shells the Marines could actually see coming toward them.

Beach congestion slowed the follow-on waves, until boat coxswains had nowhere to land, often broaching their landing craft in the heavy surf, adding to the confusion. Having no other choice, Turner kept pushing boats to the beach, hoping the Marines could open some lanes.

American airstrikes and naval gunfire pounded the Japanese defenses, but only a direct hit could silence the guns. Amid heavy casualties, and behind a wall of supporting fire, the Marines eventually pushed inland. Elements of the 5th Marine Division eventually reached the far shore at the foot of Mount Suribachi, cutting it off from the rest of the island. 40,000 Marines were ashore by nightfall, but the price was shockingly high.

Taking Mount Suribachi

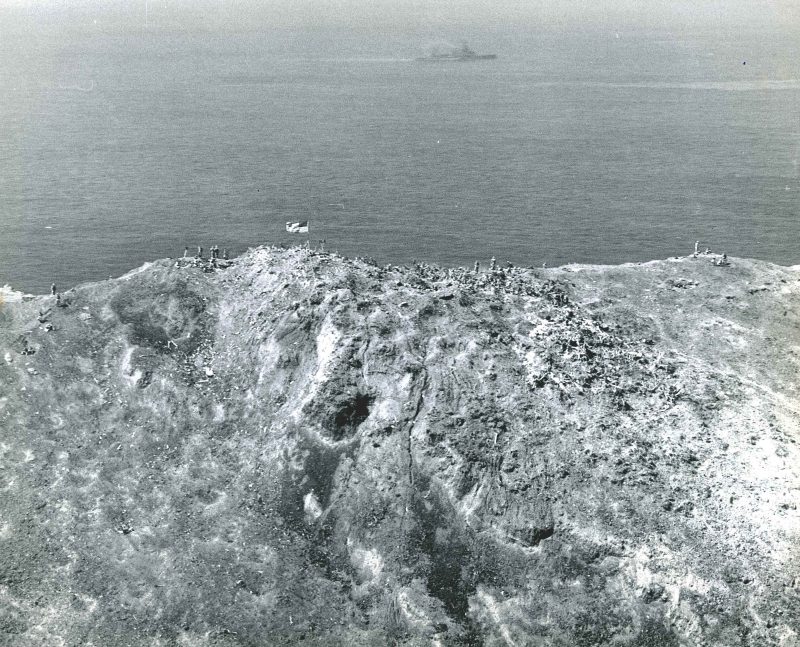

Once ashore, the Marines began the task of reducing the island fortress. The 28th Marines turned south to “Hot Rocks,” their name for Mount Suribachi. The description was accurate, as hot steam vented from the ground, which was noticeably warm. The steep slopes had been pounded by American warships and aircraft, leaving craters and shell holes across the volcano’s face.

But first, the Marines faced the concrete and steel fortifications ringing the mountain’s base. On the morning of February 20, D+1, the warships, joined by Marine artillery and strike aircraft, raked Suribachi from top to bottom. The entire mountain was enveloped in fire, smoke, and ash.

The onslaught stopped at 0830, and the Marines advanced on a two-battalion front. The Japanese defenses, seemingly unfazed by the bombardment, opened up, raking the attackers with machine gun and mortar fire. Snipers and more machine guns emerged from caves on the mountain’s face.

Rough terrain hampered the Marines’ tank support, forcing the infantry to close and destroy the Japanese emplacements themselves. Grenades, satchel charges, and flamethrowers saw heavy use as the Japanese were painstakingly cleaned out, but not before inflicting heavy casualties of their own. Taking Suribachi’s base took two long, bloody days, with most Japanese soldiers choosing to fight to the death. The 28th Marines executive officer estimated that they had taken out 50 caves and killed some 800 enemy soldiers, though he said they found less than 100 bodies. The rest were buried in their collapsed emplacements.

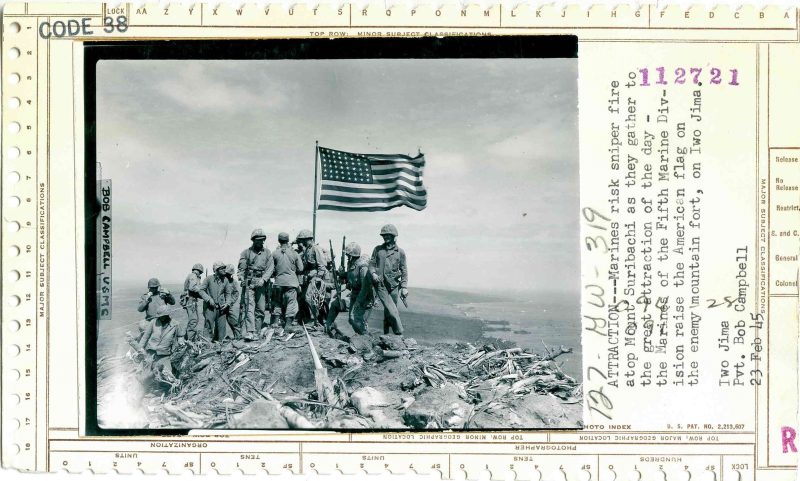

The remaining Japanese attempted to break through to their lines in the north, but most were cut down in the open as they made their dash. Marine patrols ascended Mount Suribachi the next morning, meeting little, if any resistance. The men caught the overpowering stench of Japanese bodies decaying in the hot caves as they passed.

Finding a pipe from a blown up water tank, they raised the first American flag on the mountaintop. A cheer rose from the Marines fighting below, and the ships of the supporting fleet. The 5th Division’s Brigadier General Leo Hermle said the flag on Suribachi was “one of the greatest sights that I remember in my whole life…a terrific cheer went up from the whole island, as far as you could see.” Secretary of the Navy, James Forrestal, had just gone ashore with Holland Smith to tour the landing beach. Upon seeing the flag, he turned to Smith and said, “Holland, the raising of that flag on Suribachi means a Marine Corps for the next 500 years.”

The second, more famous flag raising took place three hours later. A much larger, and more visible, flag was brought up from the fleet. Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal snapped a photo as it went up. The ensuing image became the most famous and iconic photo of the Pacific War, plastered on hundreds of newspaper and magazine covers. Rosenthal never even saw it until it published, though it won him the Pulitzer Prize. The photo is the basis of the bronze statue at the Marine Corps War Memorial in Washington DC.

Taking Mount Suribachi cost the 28th Marines 510 casualties, But the southern flank was now secure.

The Meat Grinder

Harry Schmidt estimated that he could take Iwo Jima in ten days. But he was forced to call in two-thirds of his reserve, the 3rd Marine Division, after five days. The V Amphibious Corps now advanced on a three-division front, with the 3rd in between the 5th and 4th Divisions.

The two airfields were heavily defended by concrete emplacements and makeshift defenses from destroyed aircraft frames. After the airfields, the attackers advanced up the long, rocky Motoyama Plateau. As on Suribachi, the Marines used flamethrowers and high explosives to fight the underground enemy. Artillery and airstrikes were often called to within 100 yards of the Marine positions. Marines moving up after taking out a strong point would suddenly face crossfires after only a few yards, forcing them to do it all over again. A good day’s progress could be as little as 30 yards.

The Japanese were experienced night fighters, so Navy destroyers fired star shells every minute of every night, lighting up the broken landscape. The rocky terrain was rough and unforgiving. Trying to dig into the ash under enemy fire often released noxious jets of sulfurous steam. A successfully dug foxhole was often uncomfortably warm and infested with land crabs. One enterprising Marine learned that he could bury a C-Ration can for 30 minutes, thus producing a steaming hot meal.

Casualties were horrendous, keeping the Navy Corpsmen busy right at the advance’s leading edge. Casualties among the 4th Division’s corpsmen were 38 percent. Large field hospitals sprang up in Suribachi’s shadow, working around the clock. Robert Sherrod wrote, “Nowhere in the Pacific War had I seen such badly mangled bodies.” Cemeteries were soon established near the hospitals.

The Marines fought in such places as Nishi Ridge and Hill 362C, for which they paid dearly. Turkey Knob and the Amphitheater, so named for its series of heavily defended ridges and choked ravines, flared up over and over as enemy troops emerged from their tunnel system to attack the Marines from behind. Each tunnel was found and closed with high explosives. Sometimes the trapped Japanese soldiers set charges and blew the ground out from under the Americans, taking as many as they could as they themselves were killed.

But slowly, day by day, hour by hour, the ring closed on the Motoyama Plateau. Japanese soldiers were burned or blasted from their holes or often buried alive when the Marines collapsed the entrances. They retreated through the tunnels, where they were quickly running out of food, and worse, water. The Japanese Army received the last radio message from Iwo Jima on March 23.

The Marines controlled the island’s surface by March 24, though they were still mopping up isolated caves and hot spots. The Hirawa Bay raid on March 26 was the last organized Japanese action on Iwo Jima, though the Army garrison would be cleaning up stragglers well into April. General Schmidt’s estimated 10 days turned into 35. General Kuribayashi’s body was never identified. He may have led the last raid, or he may still be buried under Iwo Jima’s volcanic rock with most of his men.

Aftermath

A few hundred Japanese soldiers survived from the original 22,500. The rest were consumed by the orgy of fire, steel, and lead. The Americans suffered 24,053 casualties, including 6,140 dead. Iwo Jima was the only Pacific War battle in which the Japanese inflicted more casualties than they suffered. Of course, most of theirs were deaths.

Three Marine divisions had been mauled, as much by the terrain as by their enemies. Two years of defeats had taught the Japanese how to fight the Americans. They showed that at Peleliu. They showed it at Iwo Jima, and they would soon show it on Okinawa. They couldn’t win, but they could extract the heaviest price possible.

But the US Marines cemented their reputation as a fighting force par excellence. Some 80,000 fighting men were crammed into an arena that measured eight square miles. There were no true rear areas, at least until the last Japanese heavy artillery was silenced on March 11, or even, one could argue, until the Hirawa Bay raid was defeated on March 26. Heavy, intense fire was the norm everywhere, and the ground favored the defenders in every way. But the Marines got it done, just as they had everywhere else in the Pacific.

The seven weeks on Iwo Jima produced 24 Medal of Honor recipients; 10 of those were awarded posthumously.

Questions

Iwo Jima was perhaps the most savage campaign of the war. Was it worth the sacrifice? The American public and their leaders soon asked those questions. The government tried to keep a lid on the shocking casualties, but word soon got out, and people demanded answers.

Perhaps surprisingly to modern readers, the war correspondents who were present turned the tide of public opinion. They were frank about the tactical problems the Marines faced, namely a supremely determined enemy fighting from an underground fortress. They wrote about the Marines’ bravery, spirit, and fighting prowess. Criticism of Iwo Jima soon turned to national pride, as Rosenthal’s ubiquitous flag raising photo turned into a major war bond theme. Only a few naysayers remained, including General Douglas MacArthur, who had hoped to make political hay at the Navy’s expense.

Army Air Forces Commander General Henry “Hap” Arnold made his case for Iwo Jima’s importance publicly, namely the need to support the strategic bombing campaign. How did that end up? Was Iwo Jima worth the price? On March 4, 1945, 22 days before the organized fighting ended, a damaged B-29 bomber made an emergency landing on Iwo’s southern airfield. The plane would have otherwise been forced to ditch at sea, with questionable prospects for the crew.

The war’s ensuing five months saw 2,251 damaged B-29s land on Iwo Jima. Some 20,000 American airmen accounted for at least one emergency landing there. We can’t say that all of those airmen would have otherwise died, but we do know that many of them likely would have. Many more were saved by the long range P-51 fighter escorts flying from the island, especially when weather patterns forced the B-29s to attack at low altitudes to hit their targets.

Historians still debate whether Iwo Jima’s benefits outweighed the cost. That question will likely never be entirely settled. But a B-29 pilot emphasized one viewpoint when he said, ‘Whenever I land on this island, I thank God for the men who fought for it.”

As for the Marines, a veteran of the campaign perhaps said it best when the United States officially returned Iwo Jima to Japan in 1968: “I’ll be damned if I help them take it again!”

The Japanese government opens Iwo Jima to visitors one day per year. The island may only be visited through a government approved tour agency. All Americans who were previously interred on the island have been repatriated to cemeteries in the United States. The Japanese government continues the search for their countrymen’s’ remains.

Battle of Iwo Jima: Attributions

This narrative was sourced from the following:

- Iwo Jima: Amphibious Epic by Lt. Col. Whitman S. Bartley, USMC; Historical Section, Division of Public Information Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1954, Via Hyperwar.

All maps are from this source as well.

- Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944-1945, by Ian W. Toll. This the third installment of his outstanding and very readable Pacific War Trilogy.

- Iwo, by Richard Wheeler, a 5th Division Marine who landed on D-Day and helped take Mount Suribachi. This book was my first introduction to the Iwo Jima Campaign as a curious teenager. I still return to it.

- Finally, I drew upon my own graduate work on World War II amphibious doctrine and operations.

0 Comments